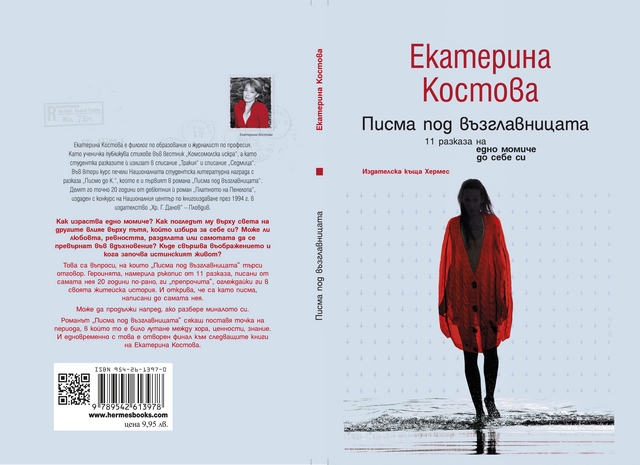

The Ship of the Alvares Family

part of the novel “Letters under the Pillow”, Ekaterina Kostova, (Hermes, 2014 )

He had his home, a wife and three daughters. He lived under the skies of Havana like a real caballero. Every winter, when the temperature outside dropped as low as 15 C, Sophia, his wife, took out his trenchcoat from the wooden chest and made sure he put it on for work in the morning. Lazaro, she told him, push your glasses up your nose and don’t forget to don your trenchcoat, a horrible wind is blowing outside. And before she could turn back to the breakfast she was preparing for the children at exactly 6.30 am, he had already plunged his arm in one sleeve. Goodbye, Sophia, he would call out while closing the door behind him. His wife woke the girls, dressed them and supervised them so they ate all the slices of buttered bread and jam, slapped their bottoms if they gave up eating midway, send hem first to kindergarten then – to school.

Afterward Sophia was alone at home – one of those Havana houses with a little front staircase, with a wooden door and brass ring on it, with a big round doorbell and a plate: family Alvares. The room you entered once you have stepped across its threshold was almost as big as a tennis court. In the middle there was a broad square table, uncovered, and around it were scattered six chairs upholstered in a blue checkered material. In one corner you could see a TV and a low yellow sofa, while the wall across led to a terrace overlooking the backyard – generally a filthy darkened place; the remaining two rooms narrowed towards two separate hallways – one leading to the family bedroom, the other – to the nursery. There were also two bathrooms each with its own shower cubicle, two squatting type closets, washbasins and oval mirrors in which every morning and evening the members of the Alvares family were trying to discover their true inner nature.

Lazaro, Sophia often startled him at such moments, your dinner is getting cold. If you wait for one more minute, you will be eating crocodile meat instead of veal. The man knew this simile well – during the first year of their marriage, when his wife still used the wrong words, for she was a Bulgarian and had only lived in Cuba for two months, he was honestly amused. But eight years later he found them rather stupid.

All right, my dear, he called out from the bathroom and saw how the mirror across gave him a sarcastic smile. Then he produced the necessary emotion so that he could acquire his usual homely though slightly strict facade and walked to the dining table. His daughters have long since finished their meal, his wife, her back to him, was intently fixed on the television screen, letting out little sparse clouds from her eternal cigarette. Lazaro swallowed the crocodile meat and contrary to all rules he poured himself a double tequila which he drank in slow gulps while staring at the black-and-white photo, hung above the front door, featuring the Alvares family in front of the Capitolia.

You aren’t a real man, Lazaro, she tapped him on the shoulder, her sharp finger nail leaving a reddish stripe on his white skin.

Why is that, my love – they looked into each other’s eyes seeking deep into their irises the darkish sands of Varadero.

Real men drink their tequila in one gulp, Sophia used to say before she poured the rest of the drink down her throat. Then she winked behind her dioptric lenses and with a swinging motion of her hip disappeared towards the bedroom. She had learned to walk like a real Cuban woman – straight-backed while her hips fluently transferred their weight of her rounded buttocks from left to right, from right to left, again and again, resembling a sand-clock on stilts. It is not that she didn’t have a good body, but under her very slim waist her hip swelled out like an excessively large balloon. This is because I gave birth to your three wonderful children, she smiled at him when in their rare nights of lovemaking his palms roamed the mounds of her body.

Of course, my dear, the man replied and the guilt for the unawakened erotic passion engulfed him like a rap wave.

One day Lazaro didn’t come back from work. Three times Sophia looked at her watch and three times her heart jumped a somersault. She watched every single soap on TV, she send the girls to bed, she drank three shots of tequila, she smoked eleven cigarettes and almost fell asleep on the sofa, exhausted by the tension and some vague fears.

Lazaro just didn’t want to return home.

He was sitting in Toni’s smoky little pub, where 11th street crossed 22nd and the whole life of the city paraded in front of his eyes – hurried or slow, smiling or grumbling, in love or out of love. But he, Lazaro Alvares, a 39 year-old engineer at Empressa de Hydroeconomia, was out of the game.

During those hours the man had no recollection of Sophia and his three daughters, nor of his house with a den as large as a tennis court. For only a moment, the taste of crocodile meat just consumed, reached him. He needed a place to throw up.

Hey, hombre, I’m not sure if it’s the rum you serve, but I feel sea sick, Lazaro shyly smiled at him, because he had never talked to a barman like that. He felt ashamed that he could easily let himself go all over the bar where his elbows were stuck.

They all say so, Toni replied and dropped his glass noisily back in front of his client, never return your drink half-drunk, he concluded wisely.

I have no idea what you are talking about, my friend, I don’t even know why I’m here, and more interestingly, I don’t want to remember who I am, where I am from and all the rest…

I think you need a girl, Toni smiled.

A girl, you say? I have already forgotten how you do these things with girls, I’ll fail shamefully. Toni squinted his eyes at him – the man in front looked quite well for his age, his hair was still where it should be, his sideburns partly covering the cheekbones, not unlike young Elvis’s. Cuban girls liked lips as full as his. Did Lazaro have all this?

Listen, caballero, why not try? He shoved his elbow.

Why don’t you try, Lazaro swallowed the last drop of his cocktail.

Just then the door opened and in rushed a swarthy young beauty with lips so bright they were like the sunrise over the Siera Maestra mountain. The air shimmered and Lazaro could smell the quietly spreading aroma of anemones. He wanted to ask questions like who this woman was, where she came from, where she was going, but the hurricane of feelings that overwhelmed him showed him that he was at a loss for words.

Toni, my love, how I miss your kisses, her voice startled him and he could hardly find her in the whirlwind of passion that filled his body.

So, Carry, where did you disappear, damn it, could at least call before you leave. The barman was facing her and was waving his hands angrily about. They looked so funny from aside. Carry was about twenty centimetres taller than him and twenty years younger.

I couldn’t, my love, how could I know I was going away for so long… she spread her arms and pulled the barman into her embrace. Her lips left a mark on his forehead. It seemed to Lazaro that those lips were about to kiss him as well. Though it was inappropriate to stay on in the pub, he felt so good. As if he hadn’t left this place for the last eight years. He tried to get up but his leg was hanging in space irresponsive to his commands. He couldn’t find the floor. Toni and Carry were kissing as if they were the last couple on earth.

When Lazaro entered his house, Sophia woke up and jumped off the sofa.

So, Lazaro, where did you disappear, damn you, you could have called…before you leave, he finished the line for her and chuckled quietly. He had heard this line somewhere… Sophia was standing there as if she was the newly found winning ticket, the forgotten character the director had just remembered after 128 episodes. She would turn the plot in her favour, by all means. Not now, Sophia, let me go to bed – the man mumbled and tried to avoid her. He had made a few steps forward when he heard something fall behind his back. He turned round and saw it was he photo album from their first years together He hadn’t opened it for more than six years. Sophia stood there, arms hanging heavily by her body, her head askew, while the midnight Havana wind slowly found its way between her legs.

It seemed to him an eternity had passed between them. Could he move forward or backward? Let’s go to bed, he offered gently and his legs, with the utmost effort, lead the way to their bedroom. He didn’t remember when or how he had fallen asleep. He didn’t remember his dreams. Although, when the next morning he opened his eyes but did not see Sophia next to him, he thought things were the same as they had been for the last eight years. He would get up, then wash, then eat breakfast and leave for work.

Lazaro, you are a bad man, he deciphered her minute writing on the table in the den. There was neither breakfast there, nor wife, nor children around.

The man slipped into his clothes and left the house.

He came home as soon as the work bell reminded him that working hours were over. He read the paper and watched the news, the inevitable tequila double shot in front of him. He fell asleep and woke up just in time, never missing the presence of his family. On the fifth day, when water and electricity bills came pouring in, Lazaro got scared. He did not know what to do with them – never had he taken any responsibility for things at home. Then, for the first time, he asked himself where his wife and children had gone. He could go to their school to see them, ask questions there where they lived and what they did. But he had no hint of where their school was. By the end of the fifth day the fear had engulfed him. It resembled a huge cucaracha in shining black armour which was crawling towards him, eyes agog. The nearer it came the fleshier its body seemed. He had to run away. He came to his senses the moment he entered the pub on 11th and 22nd street.

Hey, hombre, Toni met him with a smile and reached across the bar to greet him. Lazaro slumped on the stool and brushed away the perspiration from his forehead.

Surely, no cucarachas here? he asked in tremor.

We had them exterminated all, caballero, the barman calmed him down reaching for the bottle of rum.

The man poured the contents of his glass down his throat and stared at Toni. For the first time he noticed that he was lame. He watched him carefully and saw that one leg was shorter than the other by a couple of centimetres. This revelation astonished him. His head filled with memories of Carry squeezing him in a tight embrace.

How is she, surprisingly, it was his voice that asked this question.

Who? Toni addressed him.

The name was Carry, wasn’t it? He tried to sound indifferent.

You actually remember her?

Yes, Lazaro said simply and handed him his glass for a refill.

The barman refilled it and handed it back. Pulling a chair behind the bar, he took a seat. He lit a cigarette and had half smoked it by the time he gave him an answer.

She left.

Really?

You heard me.

What about you?

What do you mean?

What are you going to do, I am asking.

I always stay, hombre.

His fingers were slowly putting out the fag in the ashtray. Someone has to pour out rum to men like you. This is the only thing I know how to do.

You are a lucky man, Lazaro replied.

Why do you think so, Toni’s eyes fixed his from behind the bar.

There are so many men like me who you have to pour out your rum.

He gulped down the second shot, left four pesos and left.

The next day he was 40 years old. Lazaro Alvares had noone to toast on this. Even the huge cucaracha with its shining body had disappeared from view.

The man was sitting on one of the six chairs with blue-checkered upholstery in the den which was the size of a tennis court and was trying to gather the last eight years of his life.

He counted out his wedding, the birth of their first child, the first steps she had taken, the first words pronounced, the birth of the second baby, the third one…Nothing else came to mind. It’s so bleak, it’s so bleak that I wonder if it’s me who has lost the world or the world has left me. Then suddenly he made up his mind to find her. The room was filled with the smell of anemones.

Lazaro got up and headed out. His chest expanded with power; he cut like a sailing boat into the black night.

He looked for her for a month. He looked in every little nook in Havana – every shop, every drug store, every cafe and restaurant, entered every night club and institution. He stopped people in the street and gave them her description. Then went on. His trousers turned the colour of the dusty streets in twilight, his shirt was threadbare from the scorching sun and the rain that lashed at him, his shoes were in shreds as if he were the last of the homeless wanderers on earth. He ate when hunger chased him and slept where sleep knocked him down – he discovered the comforts of chipped benched, strewn along the boulevards of the city and the soft sanctuary of the grass spread under the park trees. He drank water from the stone fountains and the building downsprouts. She was nowhere to be found.

As he opened the front door of his home and shuffled his feet to the yellow sofa in front of the TV he felt that someone had been there. His olfactory sense was sharpened as if he was an animal. Whoever had been there – now he had no strength left to even get up. He closed his eyes to submerge himself into the deepest slumber he had had for forty years.

As soon as he woke up, he saw Sophia towering over him. She wore a new light blue dress, which outlined her supple buttocks, transparent in the light. He squinted and looked again just to be sure she was there.

Are you here, Sophia, he asked just to confirm the fact.

I have always been here, my love, she said and seated herself beside him. She had prepared two glasses of tequila on the table.

What about the children?

The children are getting ready for the trip, she quipped and pushed the glass in his direction. I have to tell you something, Lazaro.

Yes? He said and sat up as he always did when he heard that adamant note in her voice.

You are not a man, Lazaro Alvares, and she blew the smoke as if to form an exclamation mark.

If you wish I’ll bottom up this shot, and he reached for the glass.

Her hand stopped him.

Just leave that. Someone should drink the way you do so that it is known there men and there men. I pity you – not because of the way you disappeared, my love, but because you came back You can’t even claim openly that you don’t need us, not out of fear, but because you are uncertain that you even have a need of yourself. You live in a vague mist, Lazaro. For forty years you have walked through people and they have walked through you, but you can’t even get in touch. It is only me who managed to steal a couple of months from your life – jus enough as to give birth to our three daughters. Stay with yourself, Lazaro Alvares. I am leaving. Then Sophia dispersed in the air like a bursting soap bubble and flew off. Bulgaria is this way, the man said and stirred. He walked around his daughters’ room, their family bedroom, the kitchen – the only thing he could discover was the album and his youngest daughter’s drawing which was signed: with love for Dad from Melissa.

I couldn’t stop them, he confided to Toni later, after his fourth glass of rum.

You certainly miss them? cautiously the barman asked.

I have to learn how to live.

I learned that after I have lost ten centimetres of my leg.

So, I am better off than you. I have only missed eight years of my life.

And Carry, he had an urge to add, but stopped himself. He wasn’t sure.

In this state of uncertainty in himself as well as in the world he populated Lazaro Alvares left the pub and disappeared into the night.

The next eight years of his life proceeded uneventfully, just like the previous ones. Lacking in emotions. The blue-checkered upholstery wore out completely, the yellow sofa turned the colour of a god forsaken moon, the TV roared, the taps leaked, and the walls of the two shower cubicles had formed countless weblike yellowish and brownish layers.

As soon as the temperature dropped to 15C and the Havana wind started blowing back to Miami the smell of sun oil and sunburnt girls, Lazaro took his trenchcoat out of the closet, putting it on in the mornings before he left his home. In the evening he took it off and hung it carefully on the very same hanger Sophia has assigned him so many years ago. So when somebody in the office asked him: how is your wife doing, Lazaro? he went on as ever, replying with a smile, thank you, my friend, she watches TV and smokes cigarettes, she has started to smoke excessively. And your daughters, Lazaro, won’t they be soon getting married? Don’t you say so, my friend, they are still little girls. Especially Melissa – she’s too young for such things, they are still having bread and jam for breakfast and drink a glass of milk before they go to bed, what weddings, for Christ sake, are you talking about.

So his colleagues smiled and walked away, because, as everybody knew, nothing could shake up the calm ship of the Alvares family.

translated by Anelia Danilova